Overview¶

Overview¶

As shown on the detailed facility comparison page, the Cori, Theta and Titan systems have a lot in common including interconnect (Cray Gemini or Cray Aries) and software environment. The most striking difference between the systems from a portability point of view is the node-level architecture. Cori and Theta both contain Intel Knights Landing (KNL) powered nodes while Titan sports a heterogeneous architecture with an AMD 16-Core CPU coupled with an NVIDIA K20X GPU (where the majority of the compute capacity lies) on each node. We compare just the important node memory hierarchy and parallelism features in the following table:

| Node | DDR Memory | Device Memory | Cores/SMs (DP) | Vector-Width/Warp-Size (DP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cori (KNL) | 96 GB | 16 GB | 68 | 8 |

| Theta (KNL) | 192 GB | 16 GB | 64 | 8 |

| Titan (K20X) | 32GB (Opteron) | 6 GB | CPU - 8 Bulldozer modules; GPU - 14 SMs | 32 |

where DP stands for Double Precision and SM stands for Streaming Multiprocessor. Before we dive in to performance portability challenges, lets first look deeper at the KNL and Kepler and architectures to discuss general progamming concepts and optimization strategy for each.

General Optimization Concepts on KNL¶

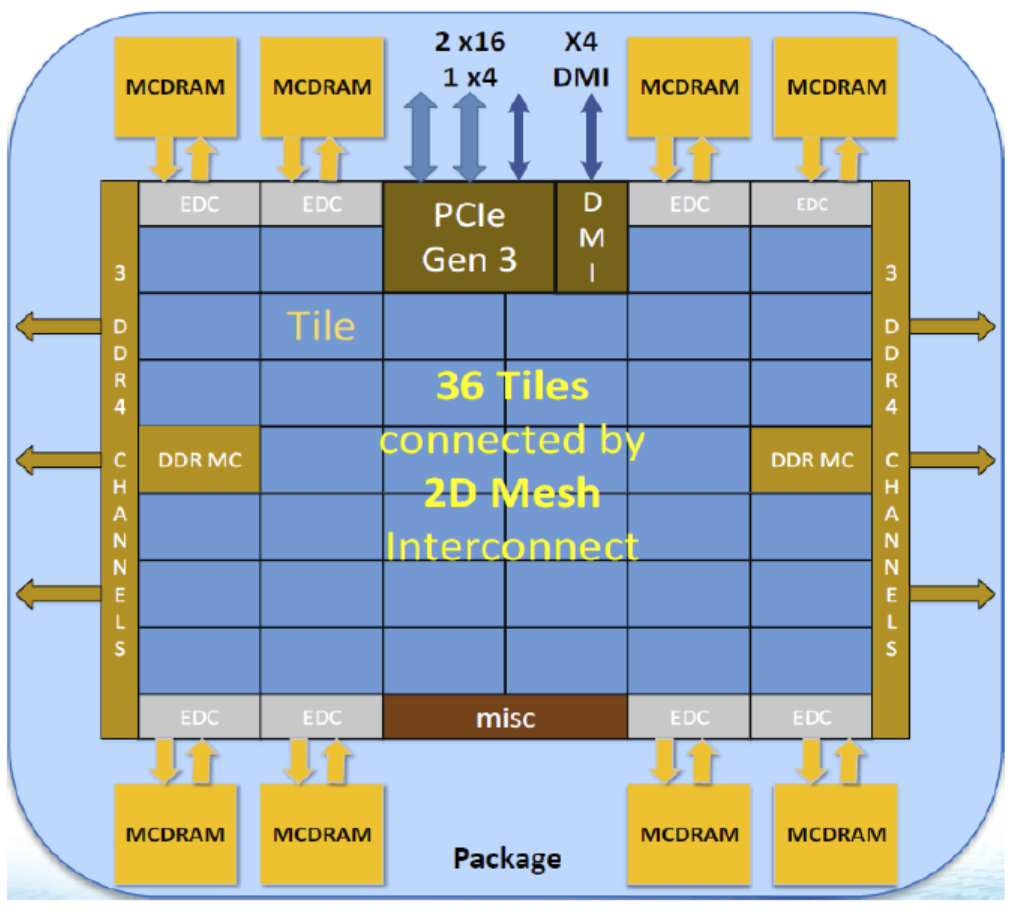

A KNL processor (Intel Xeon-Phi processor of the Knight's Landing generation) has between 64 and 72 independent processing cores grouped in pairs (called tiles) on a 2D mesh across the processor die as pictured below. Each of these cores has an independent 64 KB L1 cache and shares a 1MB L2 cache with its neighboring core on the same tile. Each core supports up to 4 hyperthreads, that allow the core to context switch in order to continue computing if a thread is stalled. Each core contains two vector-processing-units (VPU) that can execute AVX512 vector instructions from 512 bit registers (8 double precision SIMD (single instruction multiple data) lanes). Each VPU is capable of executing fused-multiply-add (FMA) instructions each cycle; so that the total possible FLOPs/cycle on a core is 32.

For applications with high arithmetic intensity (FLOPs computed per bytes transferred from memory), a performance increase factor of 64-72 can be gained by

code

that has optimal

scaling across the cores of the processor, and an additional factor of 32

in performance can be gained by vectorizable code (using both VPUs) that has multiply-add capability. Generating vectorizable/SIMD code can be

challenging. In many applications at NERSC and ALCF, we rely on the compiler to generate vector code - though, there are ways to aid the compiler with

directives (e.g. OMP SIMD) or with vector code explicitly written in AVX512 intrinsics or assembly.

For applications with lower arithmetic intensities, the KNL has a number of features that can be exploited. Firstly, the L1 and L2 caches are available and it is good programming practice to block or tile ones algorithm in order to increase data reuse out of these cache levels. In addition, the KNL has 16GB of high-bandwidth memory (MCDRAM) located right on the package. The MCDRAM has an available bandwidth of around 450GB, 4-5x that of the traditional DDR on the node (96GB available on Cori nodes and 192GB available on Theta nodes). The MCDRAM can be configured as allocatable memory (that users can explicitly allocate data to) or as a transparent last level cache.

When, utilizing the MCDRAM as a cache, an application developer may want to add an additional level of blocking/tiling to their algorithm, but should consider that the MCDRAM cache has a number of limitations - most importantly there is no hardware prefetching or associativity (meaning each address in DDR has exactly one address in the MCDRAM cache it can reside and collisions are more likely).

When instead managing the MCDRAM has an allocatable memory domain, applications can either choose to use it for all their allocations by default, or can

choose to allocate specific arrays in the MCDRAM. The latter generally requires non-portable compiler directives (e.g. !$DIR FASTMEM near the allocate

statements) or special malloc calls (e.g. hbwmalloc).

For many codes, getting optimal performance on KNL requires all of the above: good thread/rank scaling on the many-cores, efficient vectorizable code and effective use of the low-level caches as well as the MCDRAM.

General Optimization Concepts on GPUs¶

(Much of this information is taken directly from the NVIDIA Kepler Whitepaper)

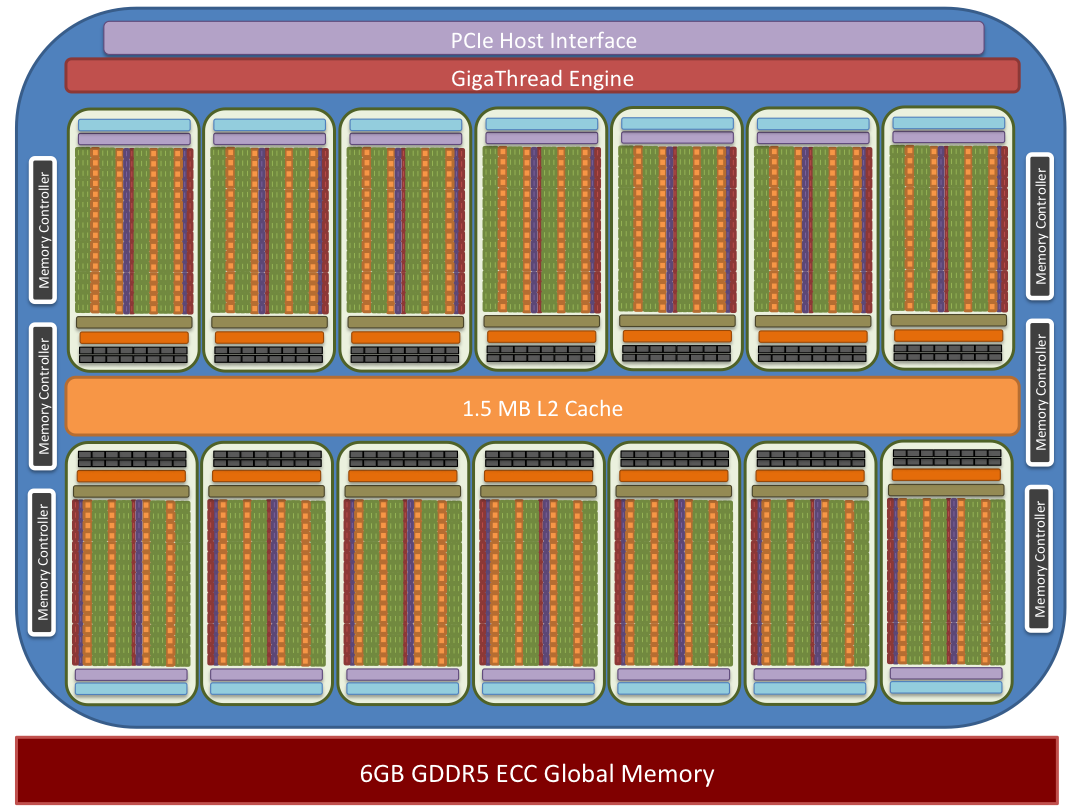

The Tesla K20x GPU is composed of groups of streaming multiprocessors (SMX). The K20x GPUs installed in Titan have 14 SMX units and six 64-bit memory controllers.

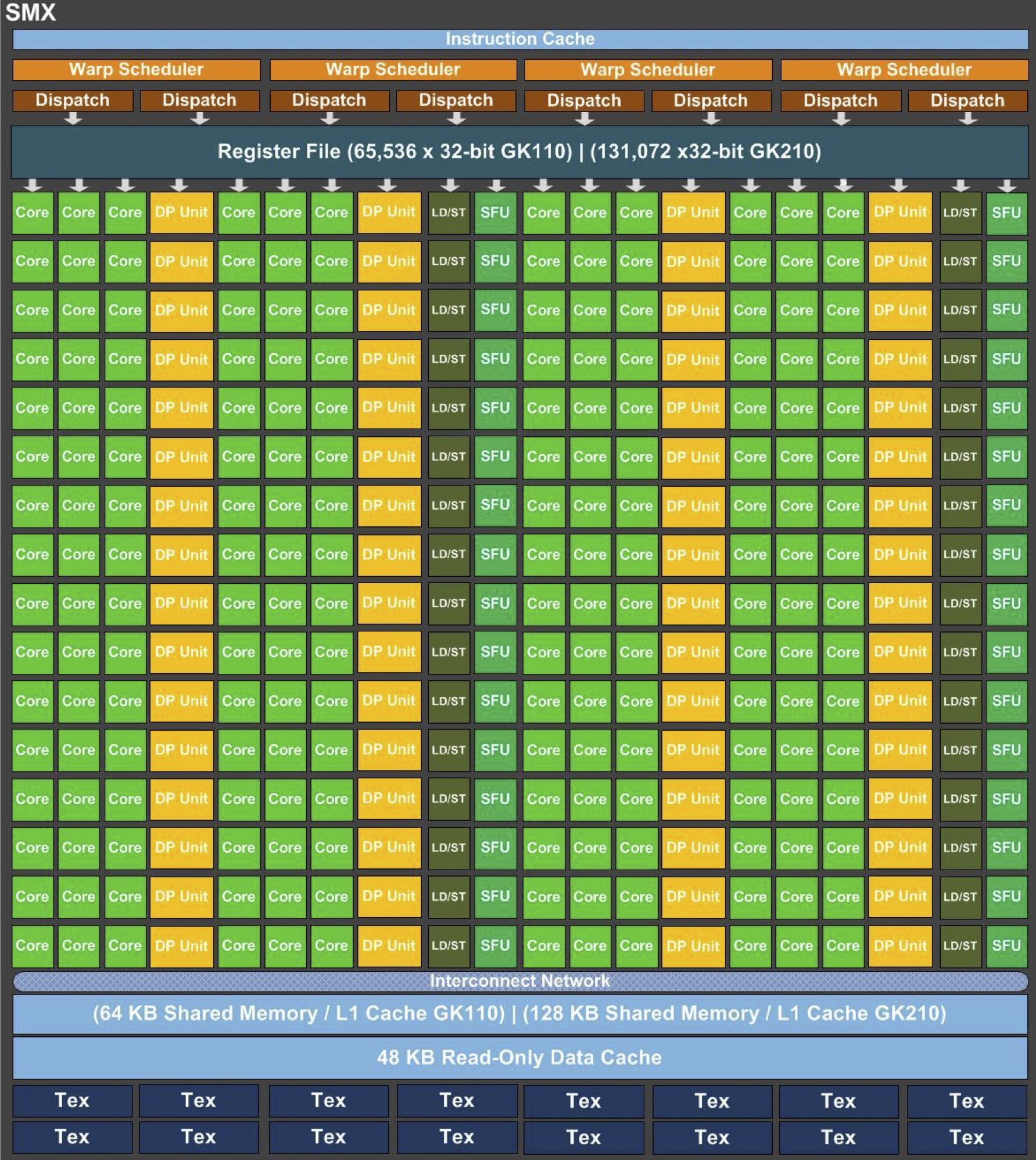

SMX: 192 single-precision CUDA cores, 64 double-precision units, 32 special function units (SFU), and 32 load/store units (LD/ST).

Each SMX contains (192) CUDA cores for handling single precision floating point and simple integer arithmetic, (64) double precision floating point cores, and (32) special function units capable of handling transcendental instructions. Servicing these arithmetic/logic units are (32) memory load/store units. In addition to (65,536) 32-bit registers each SMX has access to 64 kilobytes of on-chip memory which is configurable between a user controlled shared memory and L1 cache. Additionally each SMX has 48 kilobytes of on-chip read-only, user or compiler manageable, cache.

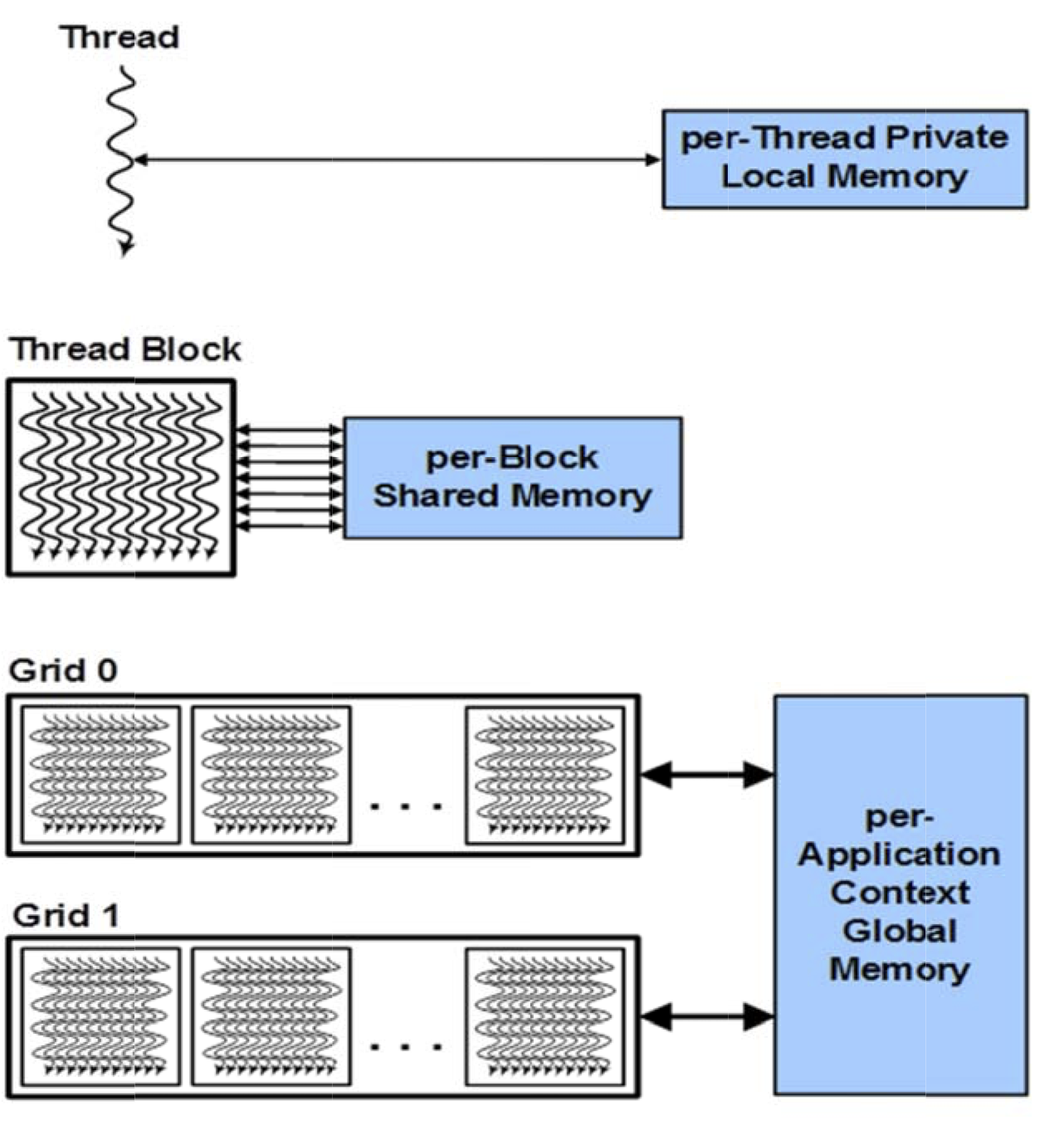

GPU parallel programs invoke parallel functions called kernels that execute across many parallel threads (these kernels may be written by the programmer using, e.g., CUDA, OpenACC, or OpenCL). The programmer or compiler organizes these threads into thread blocks and grids of thread blocks, as shown in the figure below. Each thread within a thread block executes an instance of the kernel. Each thread also has thread and block IDs within its thread block and grid, a program counter, registers, per-thread private memory, inputs, and output results.

A thread block is a set of concurrently executing threads that can cooperate among themselves through barrier synchronization and shared memory. A thread block has a block ID within its grid. A grid is an array of thread blocks that execute the same kernel, read inputs from global memory, write results to global memory, and synchronizes between dependent kernel calls. In the CUDA parallel programming model, each thread has a per-thread private memory space used for register spills, function calls, and C automatic array variables. Each thread block has a per-block shared memory space used for inter-thread communication, data sharing, and result sharing in parallel algorithms. Grids of thread blocks share results in global memory space after kernel-wide global synchronization.

This hierarchy of threads maps to a hierarchy of processors on the GPU; a GPU executes one or more kernel grids; a streaming multiprocessor executes one or more thread blocks; and CUDA cores and other execution units in the SMX execute thread instructions. The SMX executes threads in groups of 32 threads called warps. While programmers can generally ignore warp execution for functional correctness and focus on programming individual scalar threads, they can greatly improve performance by having threads in a warp execute the same code path and access memory with nearby addresses.

Programmers should also pay close attention to the placement of data in the memory hierarchy. Pinning device memory to the host memory (e.g. by

using cudaMallocHost() instead of malloc()) - allowing the system to use Direct Memory Access (DMA) transfer between the host and GPU whenever data transfer is specified - is often

significantly faster than unpinned memory access. On the other hand, pinning memory does reduce the amount of physical RAM the host CPU can page on demand, and

it takes considerable time on the host to allocate pinned memory (compared to an ordinary malloc of the same size).

In addition, using shared memory on the GPU is theoretically about 100x faster than using global memory. As previously mentioned, every thread block has (at most) 64k of shared memory.

The CUDA qualifier __shared__ can be used to specify shared memory in both statically and dynamically allocated cases. However, care must be taken to ensure that enough shared memory is available.

Challenges For Portability¶

At least three major challenges need to be overcome by viable performance portability approaches for KNL and GPU systems:

-

How to express parallelism in a portable way across both the KNL processor cores and vector-lanes and across the 896 SIMT threads that the K20x CUDA cores support.

-

How to maintain a data layout and access pattern for both a KNL system with multiple levels of caches (L1, shared L2) to block against and a GPU system with significantly smaller caches shared by more threads where application cache blocking is generally discouraged.

-

How to express data movement and data locality across the memory hierarchy containing both host and device memory in portable way.

In the following pages we discuss how to measure a successful performance portable implementation, what are the available approaches and some case-studies from the Office of Science workload. First however, we turn our attention to defining what performance-portability means.